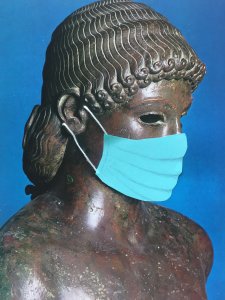

The Return of Pan: The Nakedness of Power, Panic, and Pandemics

By Mary A. Wood

Co-Chair, Engaged Humanities and the Creative Life Program

Pacifica Post Contribution, 8 April 20

“And no bird weeping a lament / no bird crying the song of its honey voice / in the leaves of Spring’s many flowers / could outrun him / Pan, in song”

–“Hymn to Pan,” The Homeric Hymns

We are hiding from an indiscriminate predator – one that cannot be outrun. Our anxiety and panic surrounding Covid-19 is real; we know that no matter how isolated our hiding place, no matter how thorough our hand washing and social distancing, it’s probably only a matter of time before we, or someone we love, are discovered by this voracious creature. As millions around the globe have experienced, this predator may spare our lives only to devour our livelihoods. In the midst of this threat, our neighbors who are deemed “essential” courageously subdue their own panic as they tend to us in hospitals, grocery stores, farms and pharmacies. Some have not survived leaving their places of safety as they provide our basic needs in the midst of a global pandemic.

The term “pandemic,” from the Greek pandēmos, meaning “all people,” traces its origins along with the word “panic” to the Greek nature god, Pan. This horned and hooved creature was born to Hermes and one of the many nymphs that he loved. Upon seeing the wild newborn, Pan’s mother fled in terror leaving Hermes to care for his half-child, half-goat son. Hermes introduced the boy to his fellow Olympians who found the curious child pleasing. Carl Kerényi explains that the common attributes associated with Pan – “dark, terror-awakening, phallic” – do not cover the range of possibilities within this god; in fact, the dark Pan may have had a twin. Pan himself may have been just one side of a more complex divine male couple.

It is the terror-awakening Pan, however, that haunts us beyond the lethal reach of the virus itself. We sense his naked appetites played out in the profiteering off of vital supplies, the insider trading of elected officials privy to early warnings, the daily preening and phallic display of power from the presidential podium, and the shameless diverting of communal resources (bailout funds) to the very rich and politically connected. The archetypal Pan seems unstoppable in his conquests, and our efforts to contain him are so often met with clever, coordinated, and oftentimes vicious attacks from his enablers. Still, we must risk approaching him in order to understand him as a multi-faceted face of nature; we must also risk understanding our individual and communal relationships to this old god.

Sukey Fontelieu did just that in her 2018 The Archetypal Pan in America: Hypermasculinity and Terror. Her work explored the underlying, archetypal energies that propel so much of the relentless violence that occurs in the United States including the 9/11 terrorist attacks, along with the Columbine and Sandyhook school shootings. Her insights are also quite prescient to our moment in time when we find ourselves faced with a different kind of terror – one that is nonetheless terrifying in its slow-motion advance on many fronts. As a newly unemployed interviewee in a recent New York Times article stated: “It’s coming for us all.” The archetypal Pan may come for our health, for our job, or for our democracy.

Like Fontelieu, Archetypal psychologist James Hillman considered Pan’s complexities in part through the writings of the first century philosopher Plutarch, who in “On the Failure of the Oracles” shouted the classic phrase, “Great Pan is dead!” Hillman asserts that this pronouncement signaled the fact that “nature had been deprived of its creative voice. It was no longer an independent living force of generativity.” When Pan is dead,

Then nature can be controlled by the will of the new God, man, modeled in the image of Prometheus or Hercules, creating from it and polluting it without a troubled conscience. . . . As the human loses personal connection with personified nature and personified instinct, the image of Pan and the image of the devil merge.

When Pan is alive then nature is too, and it is filled with gods, so that the owl’s hoot is Athena and the mollusk on the shore is Aphrodite. These bits of nature are not merely attributes or belonging. They are the gods in their biological forms.

Pan’s multiplicity and his home within an ensouled world confound our wish to simply go to war with him – even as our leaders frame our mutual unfolding tragedy as a “war,” just as was done with the so-called “war on terror.” Terror is archetypal and must be met with archetypal expressions. Our current forced global isolation and solitude may turn out to be surprisingly openings into new relationships with the horned god as envisioned by Plutarch:

But solitude, being wisdom’s training-ground, is a good character-builder, and moulds and reforms men’s souls. . . . here the mind turns to diviner sorts of learning and sees with a clearer vision. This, surely, is the reason why it was in solitary spots that man founded all those shrines of the gods that have been long established from ancient times, above all those of the Muses, of Pan and the Nymphs.

Modernity has resurrected only one Pan: the dead, zombielike Pan, who lurches forward consuming everything in his path – including those wild creatures now thought to have passed the Coronavirus onto humankind through contact in live animal marketplaces. The living Pan, embedded in every fiber of nature awaits discovery and resurrection through our solitude; he is there in the now clearer and louder birdsong, and in the now calmer waters of canals and harbors. This Pan reveals and resurrects the wilderness within all of us. His ancient song has not changed: We can never master nature – we are nature.